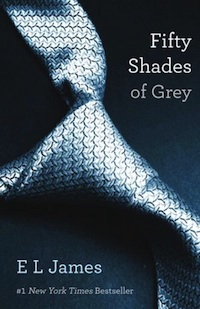

What’s next for the beleaguered book publishing business? At a time when the industry is facing unprecedented upheaval, along comes the Fifty Shades of Grey trilogy by E.L. James to make matters even more interesting. What lessons are we meant to learn from the success of Fifty Shades? Is it that sex still sells in conservative America, or that we can still be surprised by the power of ebooks to upset the market? Or is it that America may be ready for traditionally published works of fan fiction?

By now, Fifty Shades‘ fan fiction origins are widely known. The books grew out of a work of Twilight fan fiction, originally titled “Master of the Universe.” The question of how closely Fifty Shades hewed to “Master” seems to have been put to rest by an analysis done by Jane Litte of Dear Author.com that compared the texts of the two works and found they were virtually identical.

The legal issues on this issue are considerable and far from clear-cut. Most of the current debate over whether James should be allowed to profit from her work points to the 1994 Campbell v. Acuff-Rose court case which allowed for use of copyrighted material in a parody. Whether the Supreme Court’s decision will apply to Fifty Shades is debatable, and in any case unless Stephenie Meyer sues James for infringement, we’ll never know.

If these legal and ethical issues can be overcome, one has to wonder if the success of Fifty Shades is evidence of a fundamental shift in public opinion of what can be considered original art. Fan fiction as a form of literature in its own right may have reached a watershed point, fueled in recent years by two factors: the seemingly bottomless devotion of fans of the Harry Potter and Twilight series, and technology.

Science fiction and fantasy have long been fertile sources for fan fiction and indeed, the boom in popularity of these genres may have something to do with mainstream acceptance of fan fiction. A quick check at Fan Fiction.net, one of the most popular online sites, confirms that the majority of book-inspired fan fiction is based on original works of science fiction and fantasy. Harry Potter reigns supreme in this world, as wonderfully documented in this article by Lev Grossman, and at the time of my own research at Fan Fiction.net, HP was the most referenced source material with well over a half million posts, Twilight came in second with nearly two hundred thousand.

Technology is the other half of the equation. While fan fiction has probably been around as long as books themselves, it wasn’t until online bulletin boards and forums appeared that devotees of fan fiction could organize. It’s the organizational aspect that gives the fan fiction community its strength today: James built up her following by workshopping “Master of the Universe” chapter-by-chapter with a legion of ready-made fans.

There’s a generational aspect, too. The current generation has grown up used to the idea of sampling—borrowing snippets of someone else’s original content, whether in music or art—to create something that transcends the artistic intent of the components. Sampling, and its close kin the mash-up, are only possible because of advances in technology. People born to previous generations are used to thinking of art as the original work of one person. Digitized media changed that: it became perfectly acceptable to use the work of another artist—to stand on their shoulders, so to speak—and change the artist’s intent in order to create something new. Where one generation sees misappropriation of someone else’s work, another generation sees a completely valid method of artistic expression.

Imagine what the book world would look like when fan fiction co-exists alongside the work that inspired it. While it is difficult to imagine another fan fiction-based book duplicating Fifty Shades‘ heady success, it would be naïve to think that, given the validation that success bring, others won’t try to follow in James’ footsteps.

What does this tell us about the American reading public? Is this a natural outcome of a collaborative society where creative expression is valued over individual achievement? Or that fans will take matters into their own hands when a beloved franchise has run its commercial course? Or, as Grossman purports, that fan fiction is an audience’s way of providing diversity in an otherwise homogenized product, giving us the sex that a book leaves out? Should writers be content to create stories that are like paper dolls for the reader to take home and dress up as he sees fit?

Alma Katsu is the author of The Taker (Gallery Books/Simon and Schuster) and The Reckoning (coming June), dark novels of that combine history, love and fantasy. No fan fiction has been written based on them. Yet.